About the Project

- The Project: Medicine, Heresy, and Freedom of Thought in Sixteenth-Century Italy: a Network of Dissident Physicians in the Confessional Age – NETDIS

- Research Methodology and Approach

- Positive Insights on Current European Issues

The Project

NETDIS examines and interprets the connections between sixteenth-century heretical thought and the rise of modern science, exploring the local, national and transnational levels of this connection. NETDIS uses digital humanities tools to reconstruct the network of Italian physicians who developed non-conformist religious views. By exploring the nature, extent, and functions of the ties among physicians, NETDIS investigates the genesis of the freedom of thought as an embryonic value shared by most physicians in response to the spread of intolerance in the confessional age.

Heretical physicians, across Italy and in their European exiles, shaped a community of “learned dissent”. In the sixteenth and seventeenth century, inquiring into nature could correspond to inquiring into God and, therefore, scientific pursuits and religious heresy could go hand in hand. While historiography has suggested this historical problem, no one has yet examined the contexts, practices, and patterns of connection relating to humanistic, heretical physicians. Over the years of my PhD research, I have been working on filling this gap by collecting as many cases of heretical physicians as I could find in Italian archives and published sources. I have compiled a sample of 200 cases, which are gathered in a preliminary database. This database considers several aspects of the biographies of these cases and from it I have advanced conclusions, from a qualitative point of view, on the relationship between medicine and heresy. However, my PhD research only began to scrape the surface of the data I collected. The network analysis and sophisticated technologies I leverage as a part of NETDIS allow me to visualise connections among heterodox physicians and check the working hypothesis: that professional medical networks also operated as the starting point for the creation of a hidden network of dissenters, hostile to the erection of dogmatic boundaries.

Given these premises, the project focuses on four major objectives:

- Mapping Donzellini's Network

- Mapping the Venetian Network

- Mapping the National and Transnational Network

- Additional Archive Research

Mapping Donzellini's Network

NETDIS maps early-modern, medical religious dissent by first considering the experience of Girolamo Donzellini, a relevant example of a heretical doctor scarcely examined by historiography. Donzellini is a pilot case for several reasons, beginning with the relevance of his biography. Born in 1513, he was put on trial by the Inquisition five times, before becoming one of the few physicians to be sentenced to death (1587) by the Inquisition. His turbulent existence can be reconstructed thanks to a wide range of different sources. The minutes of his trials and his correspondence, along with the medical and philosophical books he published allow us to depict the experience of a dissident physician in great detail.

More important still, these sources depict a wide network of connections and show the existence of a great number of other dissident physicians, interested in both the renewal of science and religion and at whose centre Donzellini acted as an intermediary. Reconstructing and visualising this network through digital humanities tools is crucial for understanding the relationship between medicine and heresy and its relevance for the growth of European cultural identity.

Donzellini’s network’s digital map considers his heretical ties (both medical and not medical), his cultural/professional connections (both Catholic and Protestant), the course of his travels and their influence on his profile as a heretical doctor, the books he read, edited, and smuggled, and the further connections these publications opened up for him.

Mapping the Venetian Network

This first reconstruction provides a consistent range of ties, which are the object of additional investigation. Donzellini was in touch with many more heretical physicians, who, in turn, were inserted in a network of medical practice, cultural exchange, and religious dissent. This set of connections was especially based in the Republic of Venice. For this reason, after having reconstructed the case-study’s network, NETDIS maps other heretical physicians’ professional and religious bonds (in particular those of Teofilo Panarelli and Decio Bellebuono), stemming from the Republic. This work shows that heretical physicians accounted for a social beyond than an intellectual movement.

During the Sixteenth Century, Venice was one of the most prosperous European cities, a cosmopolitan land hosting people from all over, one of the most advanced printing centres in Europe, and the most dynamic Italian centre for theological debate and the spread of heretical doctrines. The Republic, therefore, was an appealing place for physicians, especially those interested in the religious reformation.

Mapping the National and Transnational Network

In the final phase, NETDIS tracks the ultra-venetian ties of the physicians who worked in Venice and the ulterior links that exile physicians built with relevant figures in the European medical and religious frame. As learned men embedded in the circuits of European culture and as dissenters interested in supporting each other, they expanded their connections to the whole of Italy and even into Germanic lands - where many doctors fled for religious reasons, often migrating again soon afterwards in search of someplace that guaranteed forms of religious and intellectual freedom. This final map visualises the personal, cultural, religious, and professional bonds of Italian heretical physicians all over Europe, considering also their religious inclination. Their religious views in particular are a crucial aspect for understanding the link between medicine and heresy as an essential factor in the rise of freedom of thought.

Additional Archive Research

The incoming phase at Verona will give me the chance to expand the research from inquisitorial sources (which are the core documents of the project) to other types of sources, such as Universities or notarial records, available in archives in the Veneto and beyond. This final collection will increase the consistency of my database and provide important details about the heretical doctors’ biographies. This information will supply the material for a further iteration of the maps produced at Stanford.

Research Methodology and Approach

Timeframe

The project focusses on the sixteenth century. The challenge is to inquire into the complicated era in which medicine was swinging between a reliance on “auctoritas” and the personal search for independent methodological and epistemological solutions. Italian universities were the centres of the reformation of medicine, and the subjects that were discussed there contributed to the radicalisation of intellectual thought. Moreover, the sixteenth century was also the “century of theology.” The theme of personal salvation was at the core of people’s concerns and this was even more the case within centres for philosophical research like universities. In the following century circumstances changed dramatically. The Scientific Revolution redefined the epistemological borders of various disciplines. Medicine and theology, which used to be conceived as deeply interrelated, started to grow distant.

Conditions also transformed in the religious realm. With the advent of the Counter-Reformation, most sixteenth-century “Italian heretics” migrated, were executed, or consciously started dissimulating their religious views.

Network Approach

Physicians were part of an intellectual community spread across Europe. They were cosmopolitan humanists, who corresponded with each other, exchanging knowledge and discoveries and travelling across different confessional zones. They were also, in many cases, unsatisfied with Catholic rituals and doctrines, hostile to the rise of confessional borders, and ready to flee beyond the Alps for the sake of professing their own ideas. The historiography has already pointed out how the mechanisms of collaboration and sharing of knowledge underneath scholars’ scientific and religious experience, could promote cultural and theological debates5. However, it is relevant to highlight that alongside these official spaces for learned debates, and often at an underground level, other forms of collaboration existed between medical doctors, whose reconstruction and visualisation has never been attempted. Physicians worked at universities, at royal courts, in more or less populous cities or in small villages, and from their position they contributed to the growth of a medical “network of dissent”. Almost wherever a heretical group arose, there was a physician leading it. These underground ties provided doctors with the ground for the development of further discussions and experimentation in science and religion.

A networked approach can therefore advance our understanding of scientific and religious kinships in the sixteenth century. It can provide information on the cultural and religious links which bounded physicians as writers or readers, publishers or smugglers, preachers or audience in the theological debate. Moreover, this approach allows us to see the origins and the transformations over the course of the century (in response to external events) of the overlapping between the religious and the scientific. It makes also possible to describe precise patterns of interaction, understanding how they were created and what their consequences were. Finally, it shows whether ties were organized in a significant way (that is to say whether they favoured forms of support among the actors, they put one individual in a particularly interesting position in terms of further ties, etc). NETDIS highlights how crucial networks were in fostering the progress of science, culture and freedom of thought, saying also something on the roots of European contemporary values.

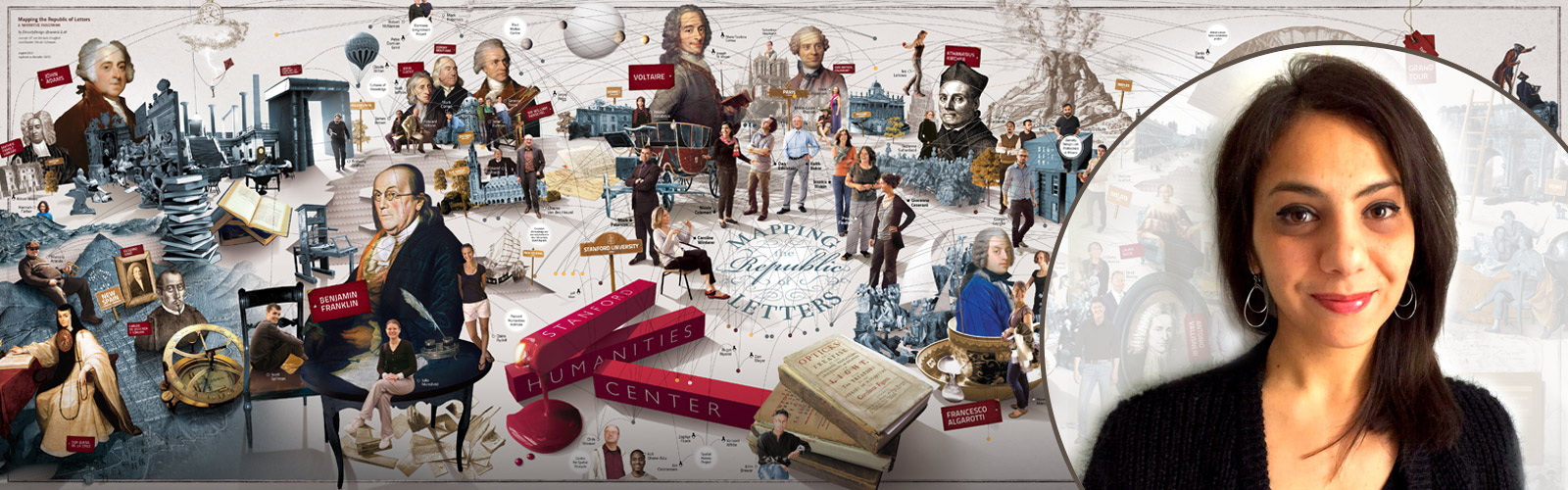

Digital Humanities

Network analysis needs the aid of advanced technological tools for data visualisation. The chance to use the platforms for the exploration of historical data developed at Stanford, the collaboration with the team of scholars carrying out DH projects at Stanford history department, and the supervision of professor Paula Findlen made it possible to analyse medical dissenters’ networks at a very deep level.

The concrete representation of the links among physicians allow me to mark the difference between interaction and potential for interaction among them. It highlights the temporality of their ties, and their impact on an individual and collective scale. It shows core and periphery, hierarchy and roles, within the network, highlighting the figures of intermediaries who bridged different networks. It provides many complementary views and indicators in terms of the sharing of medical knowledge, religious doctrines, books, etc. The digital visualisation has in itself heuristic virtues. It helps to test hypothesis as much as it favours the emergence of new research questions, and it puts one in the condition of discovering potential prejudices in the interpretation of the sources. It allows to match in an innovative way different fields of study (i.e. history of medicine and religious history). It also makes possible to address history of ideas through a quantitative approach, never applied so far. In so doing, it synthesizes in a graphic and accessible dress, decades of studies on the history of the Reformation.

Positive Insights on Current European Issues

The NETDIS project will have positive insights for several ongoing difficulties facing the EU, first of all the revival of religious violence (i.e. terrorism). The problem of religious intolerance has old roots, which also go back to sixteenth-century Christian context, as shown through the biographies of the dissenters examined in this project.

NETDIS describes the progressive rise of a community of scholars who resisted fanaticism, practiced religious tolerance, and opposed the erection of dogmatic boundaries through an open-minded attitude to science and religion.

Moreover, NETDIS will have positive insights for the spread of eurosceptic movements. The networks of medical dissenters crossed different Italian and European states, shaping a “blossom” of European conscience based on freedom of research and thought, today recognised as the common ground of European identity. The results of this project, disseminated in both academic and non-academic environments (see dissemination and documentary), will therefore provide a diachronic perspective in addressing contemporary issues.